Getting the Words Out

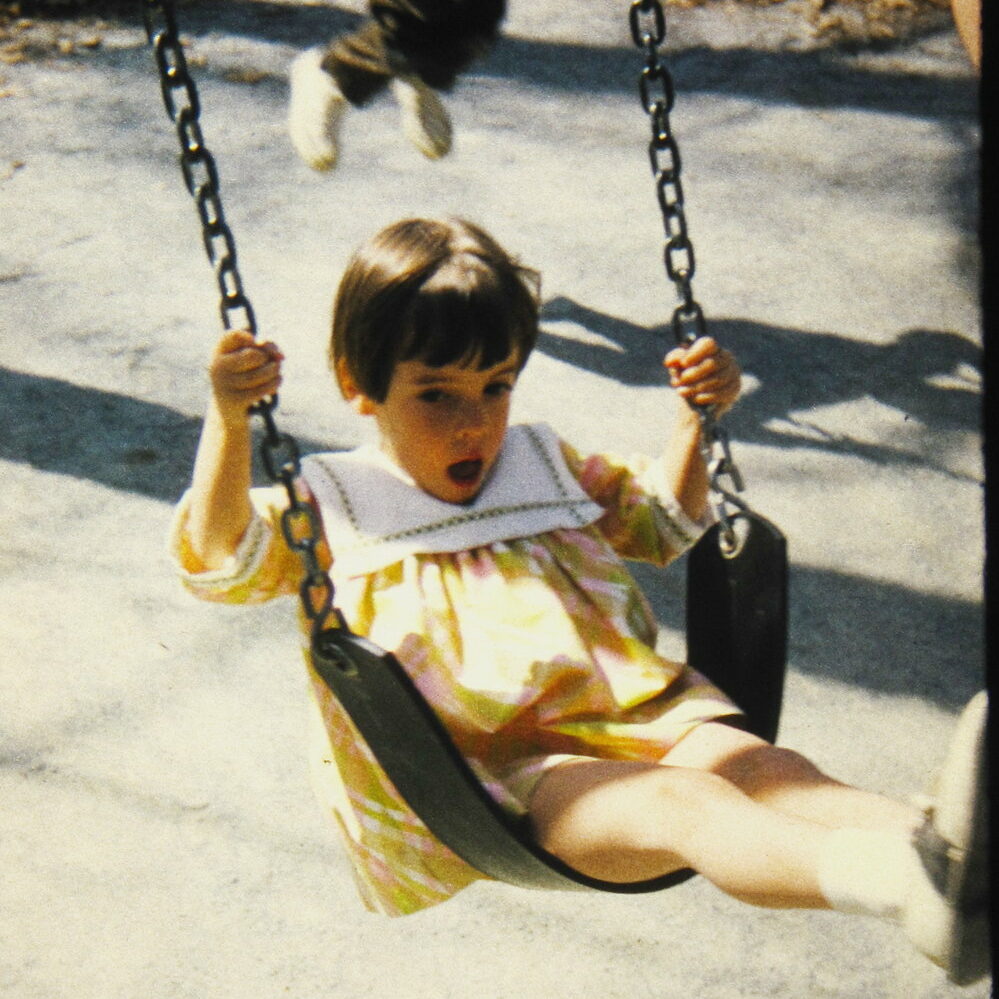

I’m sitting in a bowling alley, on the verge of tears. I’m 5, maybe 6, with a pageboy cut and a missing front tooth, and my parents have just informed me that I’m too young to join them. I am not okay with this. But I’m also powerless to do anything about it, so I sit in my hard plastic chair, stewing.

I’ve brought a bag of books to occupy myself, but I’m too frustrated to read. Instead, I pick up a pencil, open one of my books to the blank end pages and begin to write.

I write about a girl named Pam, a little girl stewing in a bowling alley because she’s not old enough to bowl. The pages fill. With every word, the clatter of pins quiets a little. With every word, my stomach unclenches.

Something has awakened in me—an awareness that words hold power. Getting them out and on the page feels salutary. I can breathe again.

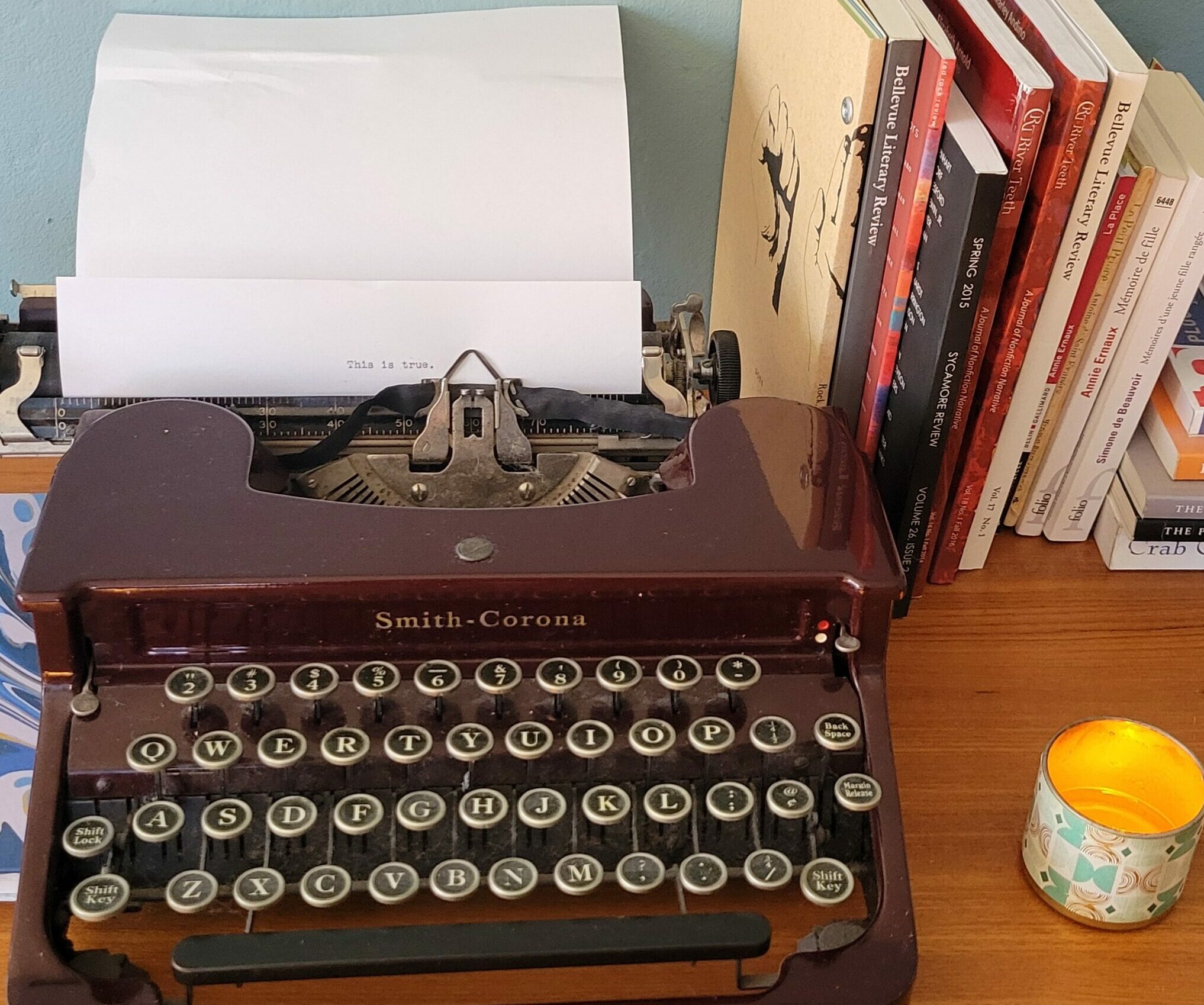

As I grow up, I continue to write, to let out words. I write in notebooks with flowers on the cover; I peck away on my parents’ Smith Corona. After college, I shake off my shyness and start a career in journalism, immersing myself in the stories of others. I write about hippies and munchkins, entrepreneurs and environmental activists. I cover fires, droughts, plane crashes, trials, elections and every manner of sport imaginable.

One night, I’m awakened by a call that my little sister is dying in a tiny corner of Africa, and something inside me breaks. Suddenly, words fail me; I’m utterly incapable of talking about her. But over the years that follow, I piece together my sister’s story until it feels like my story, too. Turning my grief into searching and searching into words feels akin to tapping a vein: word-letting.

Eventually, I leave my newspaper job, but I don’t stop chasing words. I find that words help me weather repeated pregnancy loss and, when I finally give birth to a son after years of trying, words—writing them, singing them—help me make sense of my new reality.

But as my little boy grows into toddlerhood, it becomes impossible to ignore: My son has no words. It’s perplexing, then alarming. Then we learn the truth: There’s a broken link between his brain and mouth. The road to repair will be arduous.

I lose track of how many times my son tries and fails to speak, the red-faced tantrums that spin from his inability to express himself, his anguish spinning into long-hidden family stories—generations’ worth of loss, of stifled words.

It dawns on me that silence runs in the family; its imprint lingers.

***

I would give my son the sky if that might lead him to words. I would move mountains if it would clear away his cluttered passages and untangle the knots inside his skull. But for the time being, his words stay inside, unreachable.

What will it take to free them? It will take months, years, and even then, no guarantees. It will take interwoven journeys, mother and son helping each other find answers to the same elusive question, the way to words lost and found, word-letting, release.